Abstract

This post argues that, in the field of healthcare, thinking outside the box involves taking views from the extreme and diluting it rather than trying to incrementally tinker with present policies. Various reasons are presented why we need to change our present ways of thinking about an ideal healthcare system. If the present system is broken, how do we think about the future? Examples of what may be considered as extreme thinking in healthcare systems are considered.

Shall we dare to aim for extreme goals?

How to change a system? Is it better to make incremental changes to an existing system or to examine extreme systems to see what happens if we borrow elements from those extreme systems? Does extremism trump incrementalism?

How to measure the health of healthcare systems?

How do we measure the health of an economy? How do we measure the health of a public utility system? How do we measure the health of a national defense system? All these are done by evaluating measurable end-point variables these respective systems were designed to serve. For example, the health of an economy is measured by GDP, Purchasing Power Parity, Unemployment rate, Housing starts, etc. The health of a healthcare system is measured by epidemiological variables such as infant mortality, life expectancy, mortality due to specific diseases, quality of life, etc. It is sometimes measured by economic variables such as healthcare costs and economic efficiency. It can also be measured by clinical variables such as the efficacy of disease prevention, disease treatment, or accessibility of healthcare. Using these measures, we can question the health of our healthcare systems. Are our healthcare systems sick?

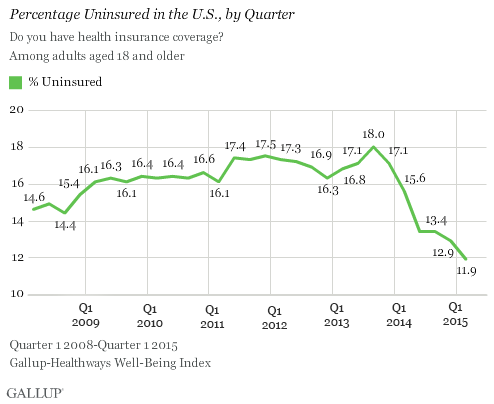

Consider, for example, an often discussed variable: disparities in healthcare delivery in countries. For example, the U.S. has large number of inadequately insured people despite the Affordable Care Act. According to the most recent Gallup survey covering the first quarter of 2015, 11.9% of adults in the U.S. remain without health insurance and access to healthcare. That is about 27 million uninsured adults.

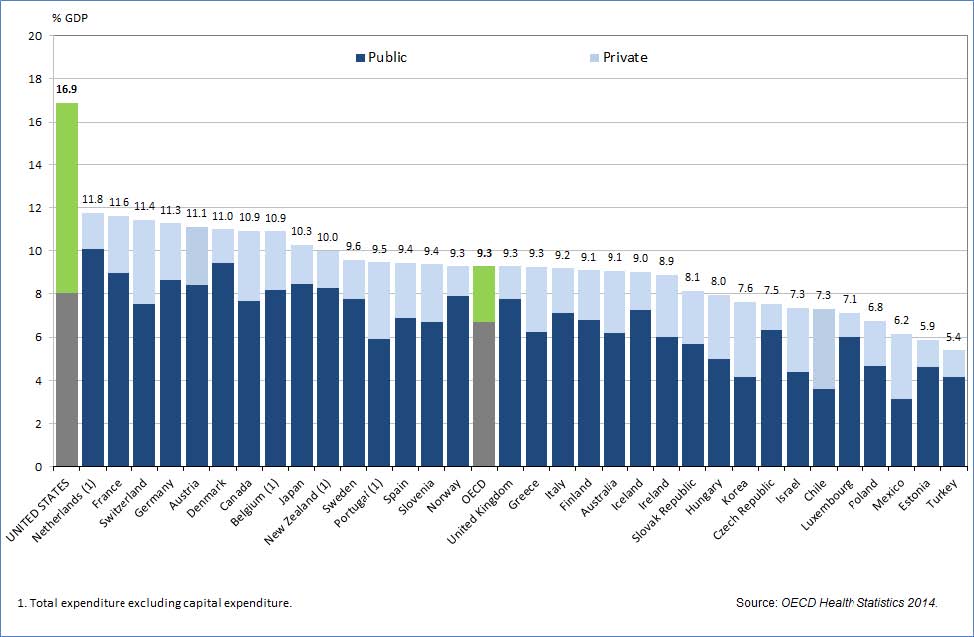

In comparison, according to the 2014 health statistics of OECD countries, nearly all of those countries have almost 100% health insurance coverage. Why is it the case that a country like the U.S. spends the most per capita on healthcare according to OECD 2015 health data,

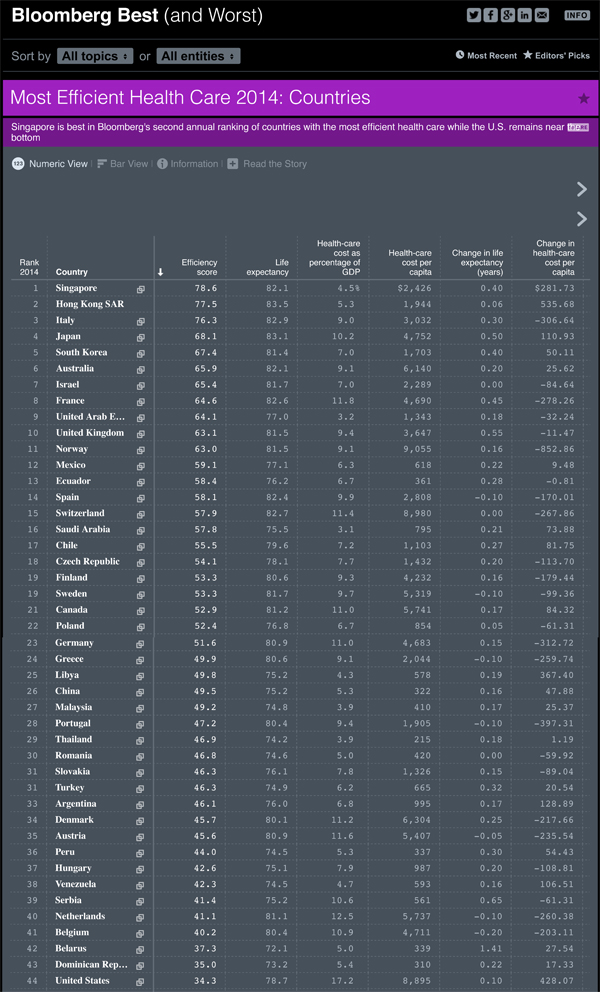

yet in their seminal paper K. Davis et al show how the U.S. population’s overall health is not even ranked in the top 10 in the world. (K. Davis, K. Stremikis, C. Schoen, and D. Squires, Mirror, Mirror on the Wall, 2014 Update: How the U.S. Health Care System Compares Internationally, The Commonwealth Fund, June 2014). Furthermore, the efficacy of its healthcare system ranks 44th in the world in the 2014 Bloomberg rankings.

Another classic paper in the New England Journal of Medicine (N Engl J Med 2010; 362:98-99, January 14, 2010) shows that the U.S. ranks 37th in the world in healthcare performance. This paper has been criticized and rebutted (N Engl J Med 2010; 362:1546-1547, April 22, 2010). If one country produces efficient cars, another country can copy the technology and produce equally efficient cars. That is the way of free markets. Yet why is it that one country produces a superb healthcare system while another country does not even care to copy that proven efficient system?

Status Quo Bias

One reason could be the politics of entrenchment. Our individual and social inertia to move from status quo is called Status Quo Bias explained best in a classic paper by Samuelson and Zeckhauser (in Samuelson W, Zeckhauser, R, Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 1:7-59 (1988)). This bias is substantial due to a combination of entrenched interests, pessimism about the future and the social psychology of individual powerlessness (one of the main causes of low voter turnout in many democratic countries). An interesting conference in 2012 on The Science of Getting People to Do Good at Stanford University’s Centre for Social Innovation discussed the impact of this prevalent social psychology on low voter turnout. A similar Status Quo bias may be infecting healthcare systems that continue to remain subpar.

We seem to be inclined to look for solutions by tinkering with existing systems. We laboriously debate and make incremental improvements and changes. Instead, I propose that we look for solutions by intellectually demolishing existing systems and examining extreme systems to see if adaptation of modified extreme systems can achieve what tinkering could not.

Extreme Systems

Today we view the primary goal of healthcare delivery as disease management. More recently, there have been some attempts at the secondary goal of disease prevention. Instead, lets imagine what would happen if we make disease prevention the primary goal and disease treatment the secondary goal. That would be an extreme system.

Consider another extreme system: today patients have to grapple with payments for healthcare. What would happen if we seek to deliver free healthcare? That would be an extreme system.

Here is another extreme system: Disease treatment is taught, trained, and practiced for particular ailments of the human body. But does not the mind play a role in the course of diseases? Evidence points that it does. In fact, since 1948, the World Health Organization has not amended its definition of health as a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity. There has been a surge in interest in mind-body medicine from people and institutions including the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, Yale University’s Integrative Medicine Curriculum, the Academic Consortium for Integrative Medicine and Health, and healthcare systems in Europe, and mainstream physicians. Then, what if we engender a healthcare system starting from medical education, and training and finally leading to a practice that recognizes the inevitable interdependencies of the body, the mind, and spirit. That would be an extreme system.

Each of these extreme systems may seem implausible. But there are clear examples of countries and healthcare facilities that borrow elements to various degrees from each of these extreme systems. The more they borrow, the higher they seem to be ranking in population health and the lower they seem to be ranking in healthcare expenditure.

Perhaps extreme systems may become the norm in the future where healthcare expenditure is minimized and population health is maximized.

Is Your Healthcare System 6P Aware?

I don’t usually comment but I gotta say thanks for the post on this one : D.